The country’s dairying industry is the most potent corporate influence on politics in New Zealand. This became even greater when former Federated Farmers president Andrew Hoggard was elected as an Act MP and immediately installed as the Minister for Food Safety. He went from lobbyist for dairying to decision-maker for dairying. Along with his sister, a lobbyist for a dairy company advocacy group, he has been able to help milk producers get their preferred regulations adopted.

A critical case study of the power of dairying lobbying and the conflicted role of Andrew Hoggard is brought to light today by an RNZ investigation by Anusha Bradley about how the industry managed to overturn plans for tighter regulations on the marketing of infant baby milk formula – see: How multinational dairy companies convinced ministers to back away from new rules for baby formula

This very lengthy analysis below attempts to highlight Anusha Bradley’s important investigation and elaborate on some details of this case study about “who runs New Zealand.” It’s a very deep dive into what Bradley’s article has revealed about the problems of lobbying and conflicts of interest.

Background: From Federated Farmers to the Beehive

Andrew Hoggard’s rise from farm lobbyist to government minister blurs the line between industry advocacy and public policy. A Manawatū dairy farmer, Hoggard served as national president of Federated Farmers (the influential farmer lobby group) from 2020 to 2023. In that role, he was a high-profile critic of the former Labour-led Government’s agricultural policies, often opposing environmental regulations and pushing to ease burdens on farmers.

In May 2023, Hoggard stepped down early from Federated Farmers – literally the next day announcing he would stand for Parliament with the free-market Act Party. Ranked high on Act’s list, he won a seat in the October 2023 election, a coup for Act given the farming sector’s traditional alignment with the rival National Party.

Hoggard’s transition from lobbyist to legislator was swift. When a National/Act coalition took power, he was swiftly appointed Minister for Food Safety and Associate Minister of Agriculture (among other portfolios) despite being a first-term MP. This put him “inside the tent” on agricultural policy decisions.

Environmental watchdogs like Greenpeace openly described Hoggard as “their man” in government – referring to the dairy/agriculture industry’s man on the inside. The implications were clear: as a former industry advocate, Hoggard could be expected to champion the same positions he had as Federated Farmers president, potentially at the expense of independent regulatory oversight.

Indeed, Hoggard signalled his intent to “remove that regulatory burden” from farmers – effectively pledging a rollback of some rules the industry disliked. Much of his early ministerial work has involved “reviews and windbacks” of policies, aiming to get farmers “back onside” with government.

One early stumble illustrated this zeal: in early 2024, Hoggard announced a freeze on councils implementing new environmental rules (Significant Natural Areas) even though the law hadn’t yet been changed, prompting outcry and a quick backtrack. Critics saw it as a sign that Hoggard might be too eager to satisfy industry wishes, even if it meant skirting normal process. In short, his background primed him to be an unabashed advocate for the dairy and farming sector from within the government – raising the stakes for potential conflicts of interest as he moved from lobbying for the industry to regulating it.

Family ties to the dairy lobby

Hoggard’s personal ties to the dairy industry’s lobby machinery compound these concerns. Notably, his sister, Kimberly Crewther, is a longtime executive in dairy advocacy. Crewther has worked at the Dairy Companies Association of New Zealand (DCANZ) for 12 years, after roles at DairyNZ, Fonterra and Meat NZ.

DCANZ is the peak industry group representing New Zealand’s dairy processors and exporters – including giants like Fonterra – and lobbies government on dairy trade, food standards, and policy issues. In effect, Hoggard’s own sister is a key player in the dairy industry lobby, directly engaging with officials on the very regulatory matters that now cross his desk.

This familial connection is a textbook example of a potential conflict of interest. Any decisions Hoggard makes on dairy regulation could be seen as benefitting (or harming) the interests that his sister represents. For instance, DCANZ regularly pushes for industry-friendly settings on everything from food safety standards to export rules.

Can Hoggard be truly impartial on dairy matters, or will he, even inadvertently, tilt toward the position his sister and former colleagues lobby for? At a minimum, transparency would demand that any involvement of DCANZ in his ministerial decision-making be carefully managed and disclosed.

So far, there’s no public indication that Hoggard has formally recused himself from dairy-related decisions due to his sister’s role. The onus has been on him to declare conflicts of interest as a minister. Given DCANZ’s frequent interface with government – and Crewther’s ongoing lobbying on technical dairy regulations – this relationship is drawing scrutiny behind the scenes.

The optics are troubling: New Zealand’s Minister responsible for food safety in dairy is quite literally the brother of the dairy industry’s regulatory lobbyist-in-chief. It exemplifies the tight-knit nature of the sector’s power structure. It has prompted concern about whether policy is being set “around the family dinner table” rather than through objective public-interest analysis.

Opting out of infant formula standards: A case study

Anusha Bradley’s RNZ story today is vitally important. This vivid example highlights the dynamics of the vested interest. It revolves around the Government’s August 2024 decision to opt out of a new trans-Tasman infant formula standard – a decision overseen and announced by Andrew Hoggard in his capacity as Minister for Food Safety. This case has become a flashpoint because it juxtaposed public health recommendations against dairy industry lobbying, placing Hoggard in the middle of a high-stakes choice.

The proposed standard: For over a decade, Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) had been working on updated infant formula regulations to apply jointly in both Australia and New Zealand. The draft new standard – over 400 pages and 11 years in the making – aimed to bring infant formula marketing and labelling in line with international best practices.

Key changes included stricter controls on what health or nutrition claims manufacturers can put on formula labels and an end to the promotion of so-called “added benefits” on the front of tins (to prevent misleading suggestions that formula can improve infant outcomes). The rules also would restrict the sale of specialised infant formulas (for babies with specific medical or dietary needs) to pharmacies or direct-to-consumer channels under health professional advice rather than on ordinary supermarket shelves.

All these moves aligned with the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes – essentially to curb aggressive formula marketing and encourage breastfeeding where possible. New Zealand’s infant formula standard was over 20 years old, so an update was seen as overdue to ensure caregivers have accurate information and protect infants' health.

Yet in August 2024, just as the new standards were about to be signed off, Food Safety Minister Andrew Hoggard and his colleagues opted out, citing potential costs to exporters. Australia will implement the stricter labelling rules by 2030, but New Zealand would go its own way – delaying any changes for at least five years while it develops a “New Zealand standard”.

The backdown stunned public health advocates. “It was surprising and very disappointing, because this has been going on since 2013… there were countless consultations,” said FSANZ board member Sue Chetwin. Experts called the decision a “missed opportunity to protect infant health, to make sure parents and caregivers have accurate information…and to support product affordability”, arguing that relying on industry self-regulation has failed. They believed the new rules were squarely about helping parents make better choices for their babies, free from misleading marketing.

What those experts didn’t see was the intense lobbying campaign behind the scenes. As RNZ’s investigative report revealed, a handful of powerful dairy and formula companies had captured ministers’ attention with a very different narrative – one of billions in export revenue at risk and hundreds of jobs on the line. This is the story of how Andrew Hoggard – a dairy farmer-turned-minister – became the central figure in a concerted industry effort to derail the infant formula reforms, raising serious questions about conflicts of interest and the government’s commitment to public health.

Big formula vs the New rules: Lobbying blitz begins

In the world of infant nutrition, all standard milk formulas are essentially the same, thanks to tight regulations that ensure safety and uniformity across brands. Special additives and flashy claims on tin labels (“probiotics for immunity”, “special A2 protein for easier digestion”) are mostly marketing hype, with little robust evidence of tangible benefits. That marketing can mislead parents and drive them to pay premium prices, so public health officials wanted to rein it in.

Notably, New Zealand has no law controlling formula promotion – only an industry-run voluntary code (overseen by the Ministry of Health) prohibiting outright advertising, making the product label one of the few marketing battlegrounds. With labels carrying so much influence, stricter rules on what can be claimed were seen as vital to “help parents make unbiased decisions” and reduce pressure on caregivers.

By late 2023, those stricter rules were finally ready. FSANZ’s Proposal P1028 ran over 450 pages, detailing everything from formula ingredients and nutritional composition to what cannot be shown on the label. Under the new standard, labels could no longer tout added ingredients or protein types (like the A2 milk protein) as selling points, since such claims might imply unproven health benefits. Infant formulas would be rendered more like plain packaging – with branding allowed, but no more pseudo-scientific boasts.

For multinational formula manufacturers, these changes looked like a threat to their lucrative business. And they wasted no time in mobilising against them. As Bradley’s RNZ story today shows, almost as soon as the new National/Act Government was sworn in after the October 2023 election, ministers’ inboxes began filling with industry appeals. On 22 December 2023, Danone NZ – one of the world’s biggest infant formula makers – emailed the freshly minted Food Safety Minister, Andrew Hoggard, and Agriculture/Trade Minister Todd McClay. “We’re very encouraged by the coalition government’s policy… not to obstruct business,” wrote Danone’s NZ operations manager, Steve Donnelly, pointedly citing the new administration’s pro-industry, anti-red tape stance.

But Danone’s praise came with a stark warning. The proposed “plain-packaging style labelling” for infant formula would make its New Zealand operation “increasingly economically unviable”, Donnelly argued, turning NZ and Australia into global outliers and making it “harder to compete globally.” If the new rules were imposed, Danone might face an “unavoidable choice to relocate our New Zealand operations to one of our other 22 international sites”, he warned – a thinly veiled threat to quit NZ, taking jobs with it.

Milking the System: How the dairy lobbyists influenced Hoggard

Danone’s alarmist message set the tone. Andrew Hoggard was now the regulator being lobbied by the same industry he once championed. By February 2024, Hoggard was hearing not just from individual firms but from their collective lobby groups. He met with the Infant Nutrition Council (INC), which represents 38 formula manufacturers across Australasia, to hear out wider industry concerns.

Behind closed doors, other players made their pitches too. Kimberly Crewther, executive director of the Dairy Companies Association of NZ – and notably Andrew Hoggard’s own sister – emailed Hoggard’s office with DCANZ’s view. She disputed FSANZ’s rationale that putting ingredients on the front label implicitly claims a health benefit, calling that a “nebulous justification” not backed up by regulators elsewhere. In DCANZ’s opinion, if global rules didn’t explicitly ban such ingredient mentions, why should New Zealand go out on a limb to do so?

Bradley’s article today shows that by mid-2024, the lobbying was in full court press. Despite the flurry of meetings and submissions, FSANZ released the finalised infant formula standards with all the controversial provisions intact in June. The industry was dismayed that none of their primary “sticking points” had been removed. With time running out, formula companies shifted to a new strategy: convince the government to exercise its right to opt out. Under the Australasian food treaty, NZ ministers could refuse to adopt an FSANZ standard – but doing so was rare and diplomatically awkward. To justify such a move, ministers would need to cite a valid reason (trade impacts, for example) and ideally rally support from political peers.

Corporate lobbyists for milk: Blackland PR enters the campaign

Danone ratcheted up the pressure. When initial meetings with Hoggard failed to produce immediate assurances, according to Bradley, Danone brought in professional reinforcements. In May 2024, Nick Gowland, a director at lobbying firm Blackland PR, reached out to Hoggard’s office on Danone’s behalf. “They’ve asked me to keep you updated so Ministers fully understand the likely consequences,” Gowland wrote, underscoring that “Danone global may well decide to move its NZ operation. A $1 billion export industry is at stake.”

This explicit warning – that New Zealand would lose a huge chunk of export revenue if the rules went ahead – was dropped directly into the minister’s ear via a hired lobbyist. Gowland soon arranged a second meeting between Hoggard and Danone, this time with lobbyist Maria Venetoulis, Danone’s legal/regulatory director (also INC’s chair).

Government officials at MPI, for their part, still supported the new standards. Ahead of that May meeting, MPI advised Hoggard that FSANZ had followed a “robust regulatory process” and that the outcome would ensure that products remain safe. MPI saw no need for a formal review – its analysis suggested most formula labels wouldn’t even need to change under the new rules, and it emphasised the rules’ overarching goal to “protect infant health and safety”.

But such reassurances from regulators were drowned out by the industry’s dire prognostications. Danone was not placated: even if many of its product labels would technically comply, the company was laser-focused on protecting what it called its “golden ticket” – the Chinese market. It also found a sympathetic ear in Andrew Hoggard, whose instincts as a farmer and exporter made him wary of undermining such a profitable trade.

High-stakes influence: Ministers, lobbyists and the push to opt out

By June and July 2024, the lobbying campaign kicked into overdrive and expanded to New Zealand’s highest political offices. Danone didn’t stop at Hoggard – it went straight to the top. In late June, Danone escalated its outreach to Prime Minister Christopher Luxon and other senior ministers.

Internal communications obtained by RNZ show that on 30 June, Danone’s Maria Venetoulis wrote to PM Luxon, copying in a raft of key figures: Deputy PM Winston Peters, Minister Shane Jones (both NZ First), Agriculture Minister Todd McClay, Finance Minister Nicola Willis, and others. She expressed relief that Hoggard “is doing everything he can” to seek a review of the standards, but urged that “ministers at all levels must be made aware of the severity” of the issue.

In a follow-up letter in mid-July, Venetoulis again messaged Luxon and company, warning that “a $1 billion export industry and [consumer] choices are at stake.” The message to the Prime Minister was clear: stick with these rules and New Zealand’s economy will take a hit.

According to Bradley’s investigation, Danone’s aggressive lobbying appeared to be working. Finance Minister Nicola Willis went on Newstalk ZB radio and openly sided with the industry’s position. Willis – effectively the government’s #2 minister – declared there was “no way” New Zealand would support the infant formula standards as written because “exporters are too important,” indicating the government would seek a delay or review instead. It was a striking public statement, suggesting that even before formal discussions with Australia, New Zealand’s top leadership was leaning toward bowing out. Industry lobbyists could hardly have asked for a better signal. Indeed, RNZ’s investigation noted that by this point “it seems they have already persuaded” Willis to their point of view.

Corporate lobbyists for milk: Cosgrove & Partners get involved

The final lobbying frenzy unfolded, with Hoggard having a last-minute meeting with a2 Milk Company executives and a lobbyist from Cosgrove & Partners (the firm headed by former Minister Clayton Cosgrove). This was a2’s chance to personally drive home its fears to the minister. After this, Hoggard’s staff remained in close contact with industry reps.

Even within government, there were conflicting views. The Ministry of Health – concerned with nutrition and child wellbeing – reportedly held a different perspective on what should happen next, compared to MPI and the ministers driving the opt-out. And then Synlait, a key New Zealand formula processor, joined Danone and a2 in urging Hoggard to opt out. In essence, the loudest voices in Hoggard’s ear were all saying the same thing: protect our exports at all costs. And those voices were coming not just from companies but from inside his own political team.

On Monday, 5 August 2024, the issue came to a head. Cabinet met on the 10th floor of the Beehive to decide New Zealand’s stance. It was now up to Prime Minister Luxon and his senior ministers to make the call. They did not surprise the industry. Hoggard’s colleagues agreed to opt out of the joint standard, citing “third country trade grounds” – essentially, the risk to exports to markets like China – as the formal justification. More than a decade of binational work went down the drain with that single decision. New Zealand would chart its own course: Hoggard announced the country will develop its own infant formula standard over the next five years instead.

Bradley’s investigation shows that within the hour, the industry knew it had won. Hoggard’s office was on the phone to Danone about 30 minutes before the public announcement, giving the company a heads-up. And just two minutes after the official press release went out, Hoggard’s staff forwarded it to a2’s lobbyist at Cosgrove & Partners.

Lobbying wins over public health advocacy

In announcing the decision, Hoggard made it clear that he favoured a lighter regulatory touch – trusting the industry to be truthful and parents to decide, rather than banning information on tins. (Notably, even opposition Labour leader Chris Hipkins signalled his agreement with the opt-out, reflecting a rare bipartisan reluctance to antagonise the all-important dairy sector.)

When interviewed by RNZ after the decision, Hoggard was frank about whose voice carried weight. He emphasised that a $2 billion export industry was on the line, and the companies most “massively impacted” – Danone and a2 – deserved to be heard. He denied that private profits were placed above infant health, insisting “I think it was appropriate [to hear them out]. They were the main ones that were going to be massively impacted by this”.

Hoggard noted he did not meet proactively with infant nutrition or public health advocates in the same way because, according to Bradley’s investigation “they did not request it and [his] focus was on exports.”. In his view, lobbying by Danone and others was not “aggressive,” even after months of what insiders described as some of the most intense industry lobbying seen in recent memory.

Perhaps the most telling comment was Hoggard’s offhand remark after opting out. He hoped that “Danone would reward us by bringing more business here to New Zealand”. To critics, this sounded like the quid pro quo at the heart of the matter: the government did what the multinationals wanted, and now expected the favour to be returned. The optics of the situation – a minister practically asking a corporation for a pat on the head after delivering the policy outcome it sought – were unsettling to many.

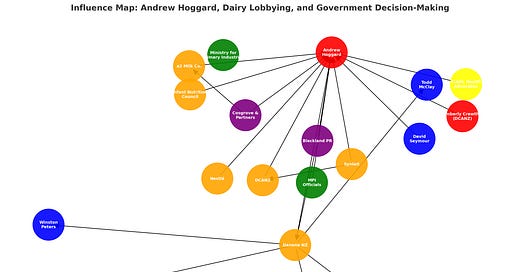

Mapping the power network behind the decision

Anusha Bradley’s RNZ article illustrates how deeply embedded the dairy industry is in Hoggard’s decision-making ecosystem. Hoggard wasn’t just another minister – he was a longtime farm lobbyist turned politician, entering office with an unusually tight-knit network of industry connections. As president of Federated Farmers from 2020 until mid-2023, he had been one of the leading advocates for dairy farmers, frequently fighting regulations on their behalf. That background endeared him to the Act Party (which champions free enterprise and minimal regulation) – so much so that Act leader David Seymour recruited Hoggard to run for Parliament as what Greenpeace activists dubbed the “dairy lobby’s inside man”.

It is hardly surprising, then, that once in power, Hoggard remained philosophically aligned with the agribusiness sector. By appointing him Associate Agriculture Minister and Minister for Food Safety, the coalition effectively placed a fox in charge of the henhouse. And, in terms of Hoggard’s sister Kimberly Crewther, intervening as the executive director of DCANZ, it might be said that “The fox isn’t just guarding the henhouse – the fox’s sister is managing the henhouse lobby.”

These potential conflicts of interest in Hoggard’s role were not just abstract or ideological – they were therefore familial. Crewther is one of New Zealand’s top dairy lobbyists. Her organisation, DCANZ, represents giants like Fonterra, Synlait, and yes, Danone and a2 Milk.

During the infant formula deliberations, Crewther did not sit on the sidelines. She emailed Hoggard’s office directly, advancing DCANZ’s stance that FSANZ’s labelling curbs were unwarranted. While there’s no evidence of any improper coordination between the siblings, the optics are uncomfortable: a minister charged with regulating an industry getting policy advice from his own sister who speaks for that industry. Neither Hoggard nor the government recused or publicly acknowledged this conflict at the time; it only came to light through Bradley’s RNZ investigative reporting.

Beyond family ties, the revolving door between industry and government swung freely. Hoggard’s former colleagues in Federated Farmers and other agri-lobby groups had direct lines into the new Government. Documents reveal that as soon as the administration changed, groups like DairyNZ (the farmers’ industry-good body) and Fed Farmers leapt to leverage Hoggard’s presence “on the inside” – firing off wish lists to him for rolling back various regulations (from environmental rules to export red tape).

One Greenpeace exposé found that dairy industry lobbyists practically drafted amendments to weaken freshwater protections, which Hoggard and his colleagues then duly introduced into law. In that instance, Hoggard was instrumental in overturning a court-ordered tightening of water pollution rules at the industry’s behest. Such episodes earned him a reputation among environmental and public interest groups as “their man in government” for Big Dairy. The infant formula standard saga only reinforces that view.

All the usual elements of modern lobbying were on display: early access to decision-makers, hired guns like Blackland PR and Cosgrove & Partners opening ministerial doors, industry associations (INC, DCANZ) providing polished arguments and legal opinions, and top politicians being courted one by one. By the time Cabinet met, every key minister from Luxon on down had been personally lobbied or copied into industry correspondence. Perhaps the campaign’s success was best summed up by an insider who told RNZ that the flurry of calls, meetings, and missives amounted to “hard” lobbying – the kind that would unsettle even the most seasoned officials. It’s clear now, from Bradley’s investigation, that the dairy industry had a seat (if not several) at the decision-making table, whereas public health advocates did not.

Public health vs Private profit: Who Won?

From a strictly procedural viewpoint, what Hoggard and the government did was within their rights. New Zealand has opted out of joint food standards a handful of times before. Protecting one of the country’s export cash cows (infant formula) from regulations seen as onerous could be framed as prudent governance. Indeed, supporters of the decision argue that New Zealand simply couldn’t afford to jeopardise an industry that brings in nearly $2 billion a year, supports thousands of jobs, and underpins our trade with China. Even the Opposition Labour Party, typically more regulation-friendly, essentially concurred with the opt-out. In that sense, Hoggard might say he was advocating for New Zealand’s national interest – ensuring the rules work for our economy, not just our babies.

But that justification rings hollow to many experts, who counter that infant nutrition and safety should never have been bartered against corporate profits in the first place. The Public Health Communication Centre blasted the opt-out as “a retrograde step”, noting it delayed much-needed improvements that would align NZ with international best practice in formula marketing. The decision, they wrote, sacrificed public health goals – like better information for parents and more support for breastfeeding – in order to keep formula companies happy. Decades of research, including a recent series in The Lancet, have documented how the $55 billion global formula industry’s “aggressive marketing” undermines breastfeeding and misleads parents, contributing to worse health outcomes. By backing away, the government, in their view, chose to prioritise dairy export revenue over the wellbeing of infants.

Even within the government, some discomfort surfaced. Rachel Brooking, Hoggard’s predecessor as Food Safety Minister (under Labour), told Bradley it was “unsettling” to witness the apparent industry influence on this issue. Brooking noted to RNZ that in her six months overseeing the portfolio, she met with the Infant Nutrition Council only once – a far cry from the dozens of meetings Hoggard had.

Hearing that Hoggard hoped for a reward from Danone alarmed her: “My hope is that the government isn’t making decisions on food safety labelling based on the hope of more economic development from one company,” Brooking remarked pointedly. She said that food standards should be about science and infant safety rather than the economics of what companies want, urging that if NZ now develops its own standard, it must not be a watered-down version dictated by industry. That sentiment captures a wider fear: by opting out, New Zealand may end up tailoring its regulations to suit its biggest companies, especially given the influence those companies just demonstrated.

Six months after the decision, RNZ reported that the Cabinet paper explaining the opt-out still hadn’t been released publicly, suggesting a lack of transparency around the government’s true reasoning. When pressed, Hoggard refused to reveal whether it was his recommendation or if he was overruled by Cabinet, calling it a “finely balanced decision”.

Either way, the outcome was the same: Big Dairy got what it wanted. The infant formula industry celebrated avoiding costly reforms – and indeed, DCANZ publicly “welcomed” the government’s move, framing it as cutting unnecessary red tape for exporters. There is little doubt whose interests prevailed.

For critics of the government, this saga has become a case study in regulatory capture. They argue it sets a troubling precedent: if a health-focused standard 11 years in the making can be scuttled at the eleventh hour due to corporate lobbying, what message does that send about whose voice counts in New Zealand policymaking? Are we comfortable with multinational companies and their lobbyists having a direct line to our top ministers, to the point that policies are changed to suit their balance sheets? And what of the subtler influence of having industry insiders in positions of power – can we trust that the public interest is truly paramount when the decision-makers see the world “through the eyes” of the industry, as one watchdog put it?

Conclusion: The Dairy lobby’s man in government?

Andrew Hoggard’s journey from farm advocacy to the halls of power was always going to test where his loyalties lie. In the infant formula standards showdown, Hoggard portrayed his stance as principled advocacy for New Zealand’s trade interests – standing up against an overzealous regulation that he felt didn’t make sense for our unique situation. Given the jobs and incomes at stake, he and his allies maintain that supporting exporters is in the public interest. To them, the end (protecting a billion-dollar industry) justified the means.

But a growing chorus of analysts, journalists, and public interest groups see it differently. They point to how seamlessly the dairy industry’s talking points became the Government’s talking points, and how quickly economic considerations overrode health imperatives. One might call it “a political drama about power and influence”.

All the elements are there: a new government keen to please business, a minister with deep roots in the sector he’s regulating, a well-organised lobby that leverages personal connections and political capital, and a policy quietly gutted before the public even knew what was at stake. It underscores a broader narrative about New Zealand’s governance: when big business knocks on the Beehive door, it often finds ministers eager to listen – and act.

Hoggard’s handling of the infant formula case has raised valid concerns about conflicts of interest and the balance of our policy process. It has also cast a spotlight on the dairy industry’s clout in Wellington. In the end, the Government did what the industry wanted, citing national interest – a justification that can be used to paper over almost any concession to business. The infants of New Zealand, of course, cannot hire lobbyists or threaten to take their business elsewhere. They rely on the government to champion their interests unreservedly. In this instance, the scales tipped toward corporate interests, leaving health experts and consumers wondering whether profit has trumped principle.

As New Zealand begins crafting its own infant formula standard (due by 2025-2030), one key question will be: Who really writes the rules – public health scientists or the dairy lobby? Hoggard insists the process will be evidence-based and aimed at infant safety (with perhaps some Kiwi-specific flexibility). However, given recent history, many will watch that process with scepticism, mindful that the same influences are still at play.

The infant formula lobbying saga of 2024 may well be remembered as the moment New Zealand’s reputation for independent, public-minded policymaking in food standards was called into question. It revealed a government uncomfortably close to industry and a minister seemingly too willing to act as the dairy sector’s champion. For a country that prides itself on its clean, green, safe image – especially in food production – that is a bitter formula to swallow.

Dr Bryce Edwards

Director of The Integrity Institute

Sources:

Anusha Bradley (RNZ): How multinational dairy companies convinced ministers to back away from new rules for baby formula, 2 April 2025

Giles Dexter (RNZ): From lobbyist to legislator: Andrew Hoggard’s vision for reform, 12 April 2024

Greenpeace Aotearoa: Milking It: How the intensive dairy industry rewrote freshwater rules in their favour, 2024

1News: Decision looms on infant formula standard, 2 August 2024

RNZ: New Zealand to implement own infant formula standard, 5 August 2024

Public Health Communication Centre: Backing off international infant formula standards: A retrograde step, 12 Sept 2024

I'm sorry to see so much hyperbole ("the infants of NZ cannot of course hire lobbyists..." in an article about possible undue influence on a Minister(s) - which was then clarified as not out of line. Obviously 'breast is best' and it's written on all the tins now - but the only argument advanced for 'plain packaging' (implied to be the main issue) is to avoid 'confusing parents' [misleading them to pay more when ingredients under strict standards are 'basically the same']. That is certainly not true of A2, nor rice milk formula or goat milk formula on sale now. I am in favour of updated technical specs to an affordable high standard and presume that's been hard work and responsible for most of the 400 pages.

In a NZ market where an estimated half of all 60k babies born annually use formula (for two years), our market at $50 a tin times two years is would be about $120-$140million ex GST annual revenue. So from the $2billion cited at risk, I can only assume that NZ public health people were trying to impose their views for this market on global consumers, who have their own regulators who clearly care what's in the tin but are not so fussed by the labelling. I find it extraordinary our public health officials think that's their business.

I think the opt out decision was 'normal', and if it were because Hoggard was more disposed to listen to producers, then I fear for so many other decisions elsewhere. Bureaucracy, and public health officials, have no financial skin in this game, and Ministers are there to try to suss out all the angles.

There is a tendency now to think that if something is advised by 'experts' it 'must' be done, and that's a dangerous view. In another policy area, I agree with the expert group who advised Winston Peters new ferries not be 'rail enabled', but politics alone won out and we persist with overly expensive, often functionally redundant, ferries. The bureaucrats (including public health experts) need to be seen as a form of 'lobbyist' and Ministers have a duty to canvass all alternative views.

Interesting and somewhat worrying commentary. Conflicts of interest are significantly more likely to arise in a tiny country, so should be even more diligently avoided with the norm being to reject positions where such conflict is almost certain to occur, with parliament providing a role model rather than what appears to be almost the opposite.

With regards baby formula, in my view "brown paper packaging" type regulations should most certainly be implemented here, but not be imposed on sales into markets where the same doesn't apply, otherwise NZ products would be at a significant disadvantage.

Moreover we'd all save more, waste less if this was extended to apply to products and services more generally, with too much misleading advertising implying product performance that's unproven or so insignificant as to be effectively worthless.